The RICHeS team recently visited the British Film Institute (BFI) National Archive at the J. Paul Getty Jr. Conservation Centre in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. The RICHeS team met with Kieron Webb, Head of Conservation at the BFI National Archive and lead for the RICHeS’ funded facilities project BFI National Archive Moving Image Conservation Research Laboratory (MICRL), and his team. The MICRL project aims to establish a state-of-the-art heritage science laboratory, the first of its kind, dedicated to moving image materials. This facility will open new avenues for cross-sector research, enable scientific analysis of film and video collections, and associated materials, through innovative technologies.

Diving into decades of film history

The BFI National Archive is home to one of the most significant film and television collections in the world, preserving material ranging from the earliest days of cinema to contemporary digital media. The Conservation Centre holds hundreds of thousands of film cans (approximately 250,000 are in the vault pictured above) alongside new data centres but beyond this the archive holds a vast array of supporting screen craft materials, from annotated continuity scripts, hand painted costume and production designs to rare promotional posters and press books that enhance our understanding of British film history.

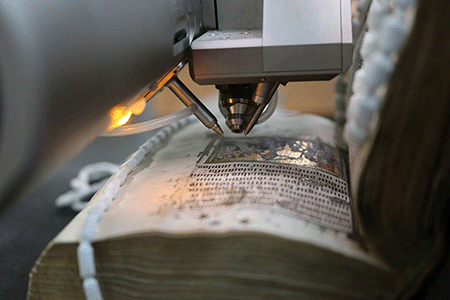

The RICHeS visit to the Conservation Centre offered a valuable opportunity to explore the conservation expertise and advanced capabilities already in place. The RICHeS team toured the Archive Film Laboratory where new equipment funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council Capability for Collections (CapCo) Fund is being used to create preservation and screening copies of original film elements and ensuring the resulting silver deposits are safely recovered.

Building the MIRCL

The RICHeS team also had the opportunity to visit the space that will become the future home of MICRL, due to launch in 2026. Currently, the space houses synchronisers that allows four film reels to be played simultaneously for comparative analysis, and innovative 3D models from the BFI’s own expert engineers has further improved the usability of the equipment.

Once complete, the MIRCL will serve as a generationally transformative hub for the sector, applying heritage science techniques to uncover, understand and preserve the physical and chemical properties of film and video collections. It will help address critical research questions and conservation challenges of moving image materials from the last 130+ years.

Revealing answers through analysis

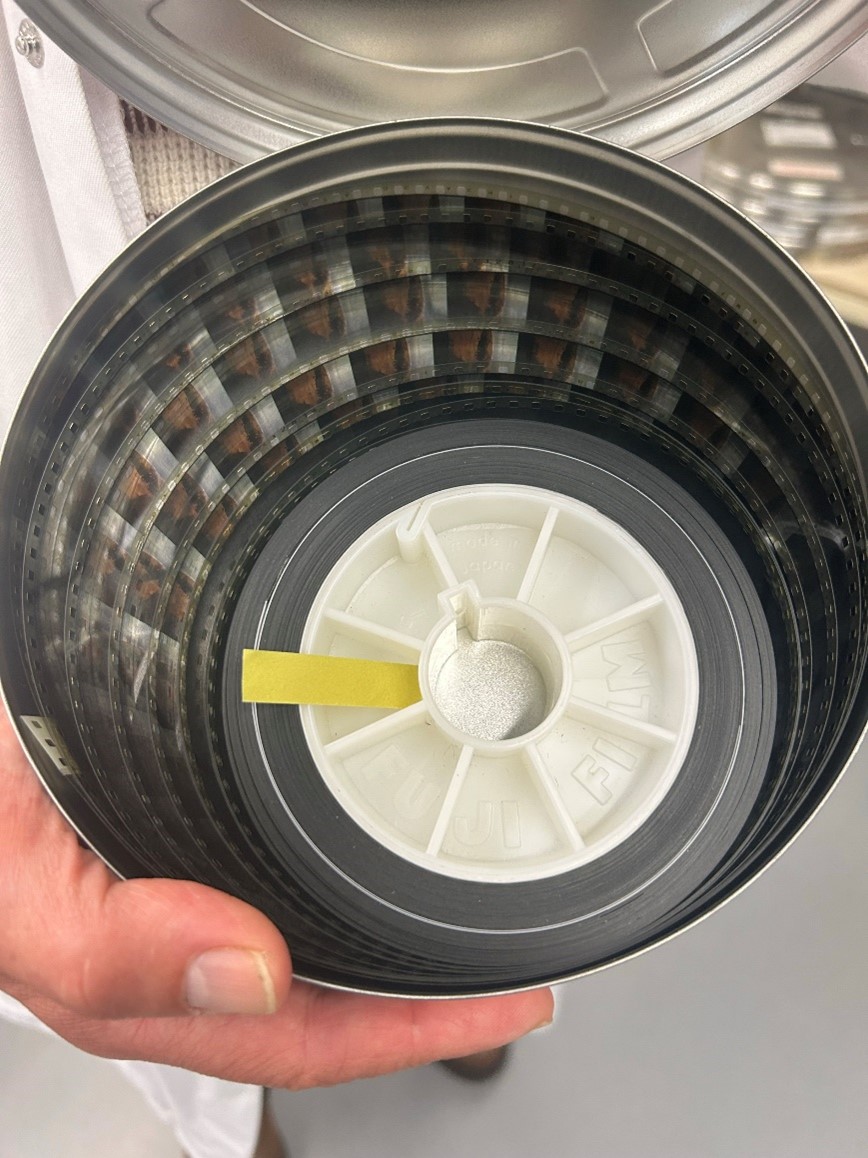

The visit highlighted how scientific methods will play a vital role in tackling long-standing preservation issues. For those working on film inspection, the cracking of film bases and fading of colour dyes is a key conservation concern. Midway through the twentieth century, ‘safety’ film, made of cellulose acetate plastic, replaced highly flammable nitrate film. If safety film is not kept correctly, it decomposes and releases acetic acid which gives off a distinct vinegary smell, known as “Vinegar Syndrome”. All preservation film elements at BFI, nitrate and safety, are kept in sub-zero storage. The new laboratory will enable in-depth analysis to answer questions on why vinegar syndrome occurs on some acetate safety films or even only some cans of the same film that were apparently stored in the same conditions. There will also be research into interventive treatments to mitigate this reaction.

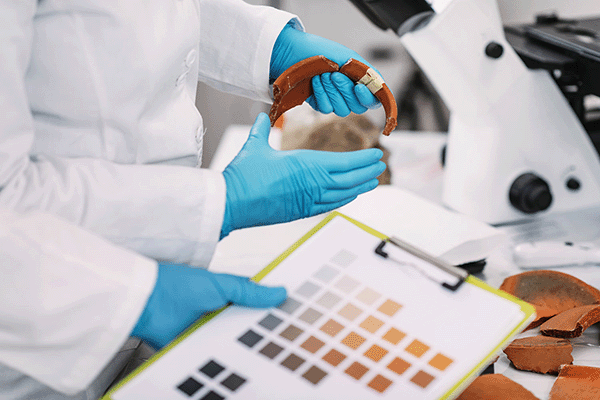

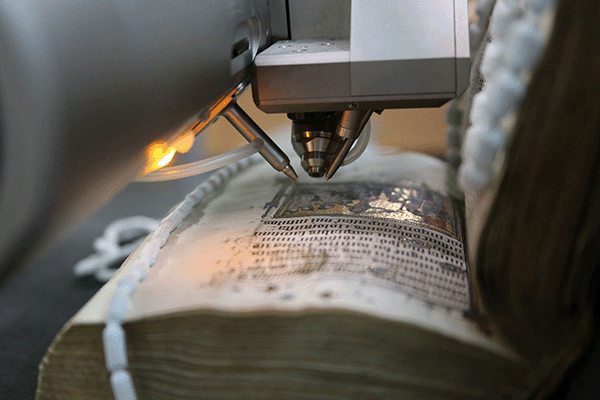

For the Archive teams utilising a new Lasergraphics motion picture film scanner, funded by DSIT’s Research and Innovation Organisations Infrastructure Fund, the new facility will support analysis of the colour used in old film. In the early twentieth century colour was often hand painted onto black and white film, frame by frame. The new scanner can capture these in up to 13.5K resolution, on which the brightness of the colour shines through. This raises questions as to what materials were used in the colouring systems, including dangerous ones such as uranium. This research will enlighten historical understanding of filmmaking, and the lives of those doing the work, as well as support the ongoing conservation.

Looking ahead: moving images research on a global stage

Once established, the new MICRL will be an internationally significant development, the first of its kind anywhere in the world, a major step forward for heritage science and moving image research. During the visit, RICHeS were delighted to hear about the international interest this project has already generated. Early collaborative work is underway with institutions such as the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland and the Diamond Light Source at Harwell campus, with particular focus on video tape degradation. The RICHeS team look forward to seeing the MICRL take shape and to the new research, partnerships, and discoveries it will make possible across the heritage and conservation sectors.

Kieron Webb shares:

“It’s an incredibly exciting time for the BFI MICRL team as we scope and fully design this transformative facility. This really is about building a research lab from scratch and it’s fascinating for us to make and build connections in the established heritage science sector to incorporate research of screen heritage collections. The response has been very supportive and positive and we can’t wait to open next year“